Page 13 - Presbyterian Connection, Spring 2020

P. 13

presbyterian.ca

SPRING 2020

Connection

MISSION

PRESBYTERIAN

13

The Checkpoint:

Restrictions on Access to Livelihood in Occupied Palestine

By Shaun MacDonald. Shaun participated in the Ecumenical Accompaniment Program in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) from Oct. 15, 2019 to Jan. 12, 2020. For three months, he lived in Hebron witnessing life under occupation. Shaun is a member of Knox Presbyterian Church in Baddeck, N.S.

Sunday, late October, 3:30 a.m. We are in a vehicle with our driver/trans- lator Rabi, on our way to Tarqumiyah checkpoint, approximately 15 km northwest of Hebron, the commer- cial capital of the West Bank and my home for the next three months. As a volunteer with the World Council of Churches’ Ecumenical Accompani- ment Program in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI), my team has been tasked with providing international protec- tive presence and reporting on hu- man rights violations in the Occupied Territories.

Only the previous day we visited the Tomb of the Patriarchs in the Old City of Hebron. Known as the Cave of Machpelah to Jews and the Ibrahimi Mosque to Palestinians, the Herodian structure above the Tomb shelters the resting place of Abraham, Isaac, Ja- cob, Sarah, Rebecca and Leah—pro- genitors of the Christian, Jewish and Islamic faiths. Since the 1967 Israeli occupation of the West Bank, the site has become a flashpoint for clashes in the struggle for access to worship between local Palestinians and Israeli settlers.

Sunday is not a day of rest in this par t of the world. In fact, it is the star t of the work week. This is why up to 15,000 people—mostly men aged 16-60—will attempt to cross the Tarqumiyah checkpoint this morning when it opens between 3:45 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. The majority are going to work as low-wage, unskilled labour- ers in Israel, even though many have post-secondary or even graduate de- grees and speak multiple languages. Outside the checkpoint I meet Fadi, a young man about my age. He has studied law in Nablus and speaks Arabic, Hebrew, English and Russian fluently. Soon we are joined by Yaya, who dreamed of becoming a French teacher upon completion of his de- gree. Both are attempting to cross the checkpoint this morning to get to their jobs as construction labourers.

“What are you guys talking about?” asks Yaya.

“The Occupation,” replies Fadi.

The fact is that, due to the eco- nomic stranglehold the West Bank finds itself in, as a result of the Israeli military occupation, there is little in the way of professional work for Palestin- ians, and these unskilled jobs in Israel are more plentiful (and pay more) than similar jobs in the Hebron Governo- rate.

The walk through the checkpoint is long. The first section takes Palestin- ian workers through two narrow tun- nels in a prisonlike corridor of steel bars, before coming to the first wall of four turnstiles. If they are open and workers are able to get through, they walk outside for about 10 metres, only to continue queueing in another prisonlike corridor. Before the next set of turnstiles, they will all be subjected to a rigorous, airpor t-style security screening. Many will be denied ac- cess, mostly for arbitrary reasons pertaining to the status of their per- mits. As a representative of Machsom Watch* told us, “It is not so much the violence, but the bureaucracy of the occupation that is so dehumanizing.” Adding insult to injury is the fact that Tarqumiyah checkpoint is inside the Green Line—when Palestinian work- ers finally pass through to the other side, they are still in Palestinian ter- ritory. They have not even reached Israel yet.

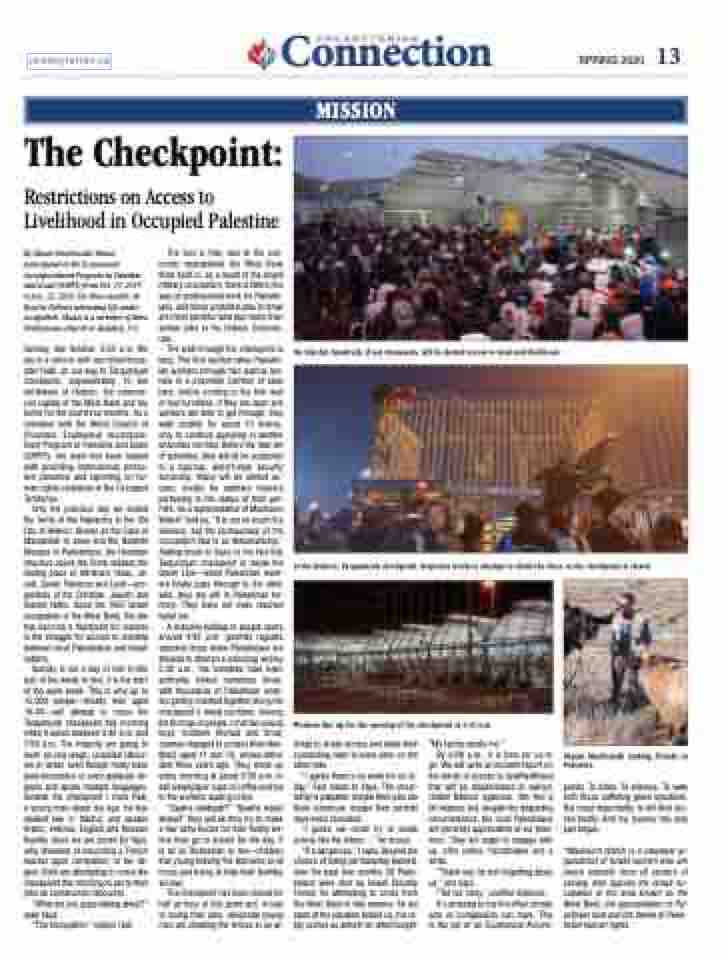

A massive buildup of people star ts around 4:45 a.m. (permits regulate selected times when Palestinians are allowed to attempt a crossing) and by 5:30 a.m., the turnstiles have been arbitrarily locked numerous times, with thousands of Palestinian work- ers getting crushed together along the checkpoint’s metal corridors. Among the throngs of people, I met two young boys, brothers Ahmad and Omar, (names changed to protect their iden- tities) aged 11 and 12, whose father died three years ago. They show up every morning at about 3:30 a.m. to sell small paper cups of coffee and tea to the workers waiting in line.

“Qawhe shebaab?” “Qawhe walad shekel!” they yell as they try to make a few extra bucks for their family be- fore they go to school for the day. It is all so Dickensian to me—children that young braving the elements at all hours just trying to help their families survive.

The checkpoint has been closed for half an hour at this point and, in fear of losing their jobs, desperate young men are climbing the fences in an at-

On this day hundreds, if not thousands, will be denied access to land and livelihood.

At the Hebron, Tarqumiyah checkpoint, desperate workers attempt to climb the fence as the checkpoint is closed.

Workers line up for the opening of the checkpoint at 3:45 a.m.

tempt to sneak across and make their connecting rides to work sites on the other side.

“I guess there’s no work for us to- day,” Fadi states to Yaya. The uncer- tainty is palpable: maybe their jobs are there tomorrow, maybe their permits have been cancelled.

“I guess we could try to sneak across like the others...” he muses.

“It’s dangerous,” I reply. Beyond the chance of being permanently banned, over the past two months 20 Pales- tinians were shot by Israeli Security Forces for attempting to cross from the West Bank in this manner. As we stare at the situation before us, his re- ply comes as almost an afterthought:

“My family needs me.”

By 6:00 a.m., it is time for us to

go. We will write an incident report on the denial of access to land/livelihood that will be disseminated to various United Nations agencies. We feel a bit helpless but, despite the degrading circumstances, the local Palestinians are generally appreciative of our pres- ence. They are eager to engage with us, offer coffee, handshakes and a smile.

“Thank you for not forgetting about us,” one says.

“Tell our story,” another implores.

It’s amazing to me the effect simple acts of compassion can have. This is the job of an Ecumenical Accom-

Shaun MacDonald making friends in Palestine.

panier. To listen. To witness. To walk with those suffering grave injustices. But most importantly, to tell their sto- ries boldly. And my journey has only just begun.

*Machsom Watch is a volunteer or- ganization of Israeli women who are peace activists from all sectors of society, who oppose the Israeli oc- cupation in the area known as the West Bank, the appropriation of Pal- estinian land and the denial of Pales- tinian human rights.